In books and contributions about Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt, depictions can be found which have influenced his reception in significant ways until the present day. The image of Karlstadt as the „negroid-looking“ dissident was firmly established by the beginning of the second half of the last century.

In 1988 there was found a printed memorial leaflet with a woodcut portrait, published in Basel on the occasion of Karlstadt’s death.

![Woodcut on the Memorial leaflet [Basel 1542]](https://karlstadt-edition.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/fig02-300x300.jpg)

Signatur: MUE Hospinian 7)

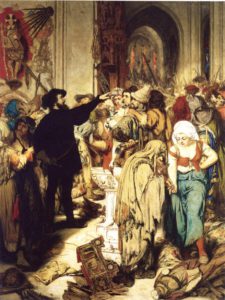

In the context of a Cranach Exhibition at the Frankfurt Städel Museum (2007/2008), the consideration first emerged of whether a 1522 dated portrait by Lucas Cranach the Elder of a clean-shaven man and its counterpart, the portrait of a young woman, could possibly portray Andreas Karlstadt and Anna of Mochau, whose wedding had taken place on January 19th of that year.1

In the summer of 1521 Karlstadt critically examined the church’s position of mandatory celibacy in a series of theses and discussed the matter critically in both Latin and vernacular pamphlets. First clerical marriages occurred in May 1521, including the public marriage of Bartholomäus Bernhardi from Feldkirch (a member of the inner circle of the Wittenberg Theologians), caused a great sensation. A widely distributed, anonymous defense of Bernhardi was attributed to Karlstadt’s authorship.

As the first of the Wittenberg Reformers to take this step, Karlstadt celebrated his betrothal to Anna von Mochau on December 26, 1521, and they were married on January 19, 1522. Through his own marriage, he wanted to set a public and constructive example; he hoped to encourage many priests, who were living in the morally-reprehensible consequences of celibacy („in the devil’s prison and jail“), to marry. Present at his betrothal in nearby Seegrehna (the home of the bride) were two wagons filled with Wittenberg colleagues and friends, among them Philip Melanchthon and Justus Jonas (who married shortly thereafter on February 9). For the wedding and the elaborately prepared feast, Karlstadt publically invited the teaching staff of the university and the Wittenberg town council. He also invited his sovereign, the Elector Prince Frederic III., with a personally addressed letter „to gracefully be present in person“.

In light of the intentional staging of this wedding, the possibility that an order of an appropriate portrait of the couple was made to his friend Cranach seems very likely. The reality that Karlstadt introduced innovations into the religious service in Wittenberg at the end of 1521 (e.g. lay chalice) and that this happened hand-in-hand with a „clothing-style staging“ should be taken into consideration here. Karlstadt’s intention was to achieve a „de-clericalization“ of his person. Alongside his decision to marry, he symbolically demonstrated his refusal to differentiate between clerics and laypeople or burghers (due to celibacy) by growing out his tonsure and wearing secular garments. As archdeacon of the Wittenberg All Saints‘ Foundation, a doctor in both canon and civil law, and longtime professor of the Wittenberg Faculty of Theology, Karlstadt and Anna von Mochau (herself descended from landed gentry), fit one another’s social status and belonged at least to the upper urban bourgeoisie of that time.

The 1522 painting by Cranach is with high probability an accurate portrayal of Andreas Bodenstein of Karlstadt. This painting, along with a re-evaluation of the history of research on Karlstadt images, unmasks the widespread image of the „dark iconoclast“ as a mere historical construct.

If this unidentified portrait indeed depicts Karlstadt, it contains multiple significances for the history of Reformation: It would be the first painting of a Reformer with a certain dating, the first painting of a married reformed cleric and an indication that Karlstadt’s critique of religious images in January 1522 was not an attack against the secular painting outside of the church.

1 See: Alejandro Zorzin, Ein Cranach-Porträt des Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt, in: Theologische Zeitschrift (Basel) 70, 2013, 4-24.